Memory through Art, Space, and Time: Dani Karavan’s Monuments in Israel and Germany in Historiographic Perspective

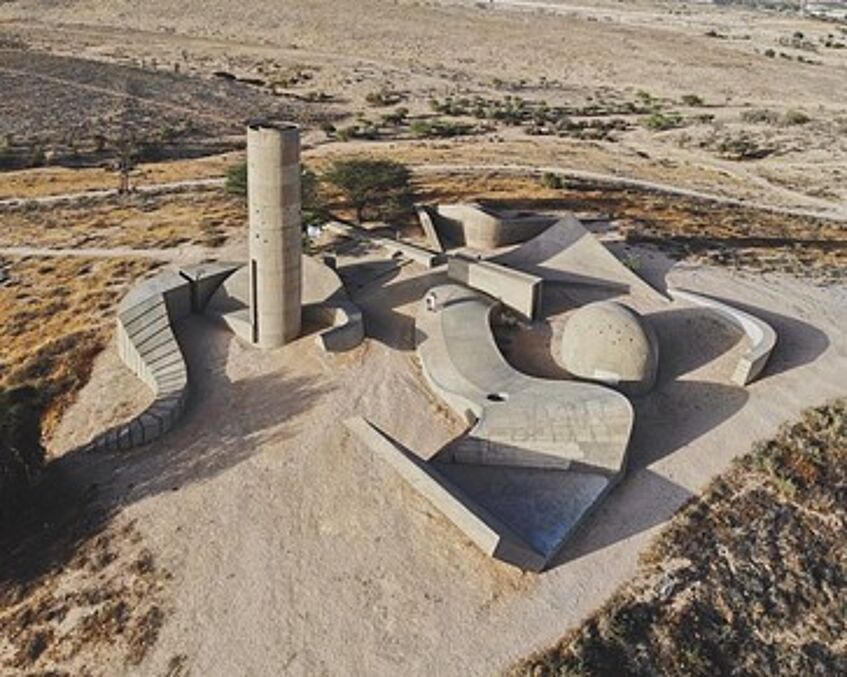

The Negev Monument (1963-1968) is a well-known site near Be’er Sheva in the Negev desert.

© Nir Tober / CC BY-SA 4.0

Grundgesetz 49 (1997-2002) consists of 19 glass panels with the articles of the German Basic Law on them.

© Michael Rose / CC BY-SA 3.0

Memory through Art, Space, and Time: Dani Karavan’s Monuments in Israel and Germany in Historiographic Perspective

von Lea Anna Berndorf

Dani Karavan (1930-2021) is an internationally acclaimed sculptor from Israel who was one of the pioneers in the field of site-specific environmental art. His artworks are often endowed with complex meanings and symbolism and invite visitors and passersby to interact with them. They are usually located in public spaces, touchable and walkable. By designing each of his artworks site-specifically, Karavan embedded them both culturally and materially in their surroundings – making him and his art an intriguing object to explore the field of memory through art, space, and time.

In my research, I focused on Karavan’s oeuvre in Israel and Germany and found, that it reflects various trends and developments within discourses of contemporary history in both countries. Although his works in Israel, such as Pray for the Peace of Jerusalem (1965-1966), a wall relief in the assembly hall of the Knesset in Jerusalem or the Negev Monument (1963-1968) near Be’er Sheva, do not necessarily align with such processes in Israeli historiography chronologically, they do represent common themes of Israeli collective memory overall.

With his determined voice against the occupation of the Palestinian territories and for a re-examination of the 1948 war with a focus on justice and peaceful co-existence, however, Karavan is to be considered a pioneer in the thematic field of Israeli-Arab relations. These issues found their way into the awareness of a wider Israeli public only in the late 1970s and 80s, initiated by a group of critical historians, the so-called “New Historians”. In an interview with, Noa Karavan, Dani Karavan’s daughter, she told me that her father had been ahead of the New Historians: “My father was dealing with this subject long before the New Historians came into being. I think he was aware of all of this already in the late 1940s when he was a member of Kibbutz Harel. […] He was aware and also very concerned and touched regarding the Arabs being expelled from their villages. So it was something he dealt with quite early in his work.”

In Germany, Karavan’s work is much more in line with the developments in the field of contemporary history and collective memory. Initially, Karavan refused to travel to Germany and said: “I don't want to put my feet on this land”, as Noa Karavan recalls. Karavan was eventually convinced to visit Germany and exhibited his work at documenta 6 in Kassel in 1977 and afterwards started to accept commissions for permanent public artworks in various German cities. Thus, he entered the German art scene at a time that marked a significant turning point in regard to German contemporary history scholarship as well as the perception of the German past in society. With works such as Ma’alot (1980-1986) in Cologne, the Way of Human Rights (1989-1993) in Nuremberg or the Garden of Memories (1996-1999) in Duisburg, he quickly built a reputation as one of the most prominent creators of site-specific environments dealing with memory. His more recent works Grundgesetz 49 (1997-2002) and the Sinti & Roma Memorial (2000- 2012), both located in the heart of the governmental district in Berlin, reflect this prominent status and even represent contemporary shifts, such as the gradual recognition of previously neglected victim groups of the Nazis, such as Sinti and Roma.